Understanding Common Causes of Industrial and Warehouse Injuries

Introduction and Outline

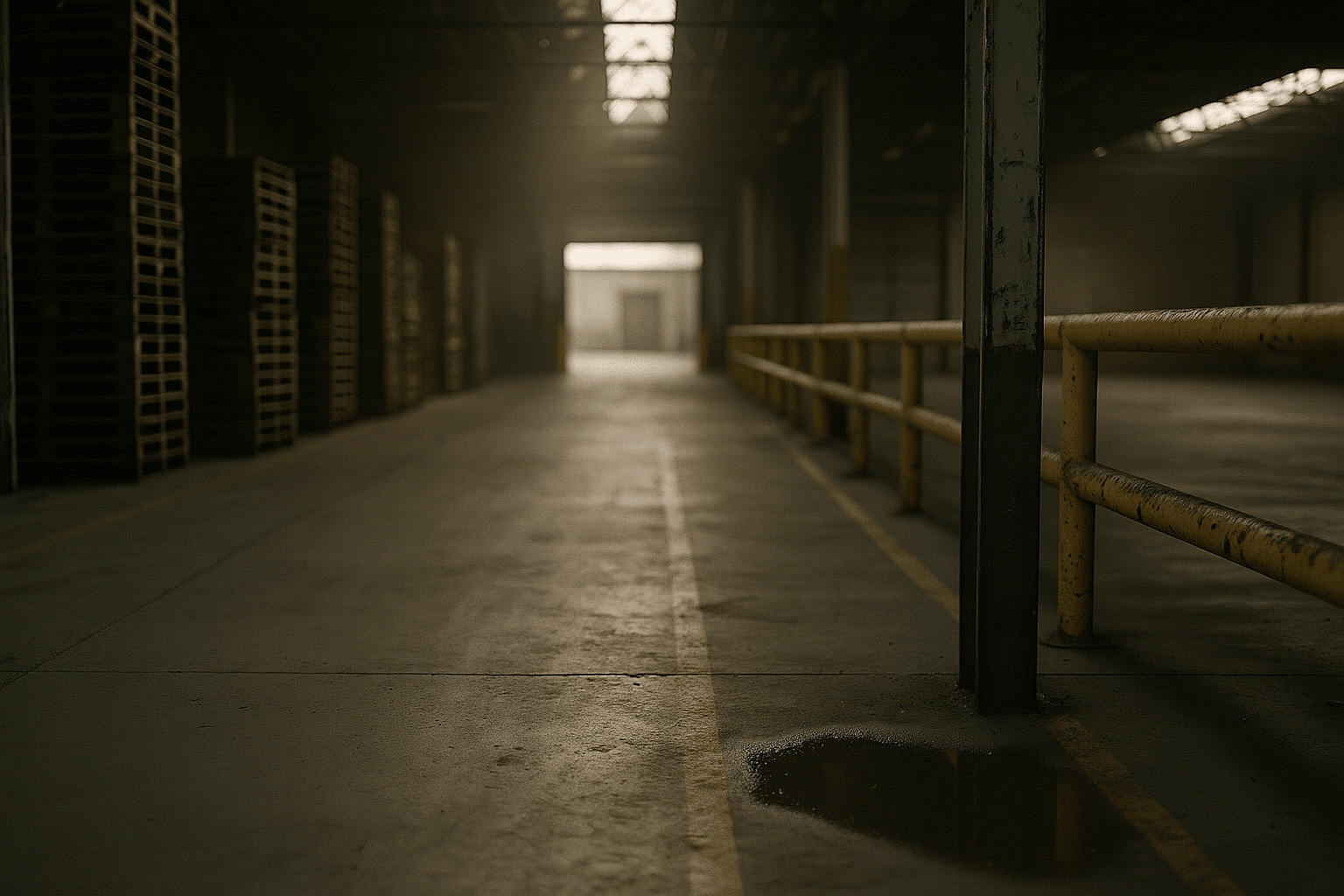

Walk into a busy warehouse and you’ll sense the rhythm: the thrum of conveyors, the hiss of pneumatics, the quiet choreography of storage and movement. That same rhythm can stutter the moment a foot slips on a damp patch, a back strains to hoist a misjudged load, or a pallet is nudged into the swing path of a lift truck. Safety, ergonomics, and accident prevention are not separate topics; they interlock like pallet corners, each reinforcing the other. In many industrial economies, regulators routinely report that sprains, strains, and overexertion injuries comprise a large share of recorded incidents, with slips, trips, and falls also prominent. Beyond human pain, the consequences are measurable: days away from work, overtime spikes, rework, inventory loss, and insurance cost creep.

This article focuses on practical, facility-level action. We compare reactive versus proactive safety, clarify how ergonomic design prevents musculoskeletal disorders before they begin, and map accident patterns to root causes you can control. We also translate policy into floor-ready tactics, because a painted line or a revised pick path, applied thoughtfully, can turn a hotspot into a non-event. To help you navigate, here’s the roadmap you can use to brief your team:

– Section 1: Lays out why these topics matter, sets definitions, and frames the scope with common injury trends and business impacts.

– Section 2: Explores core safety principles using the hierarchy of controls, with examples tailored to storage and material handling environments.

– Section 3: Dives into ergonomics—force, posture, repetition, and duration—plus low-cost adjustments that change outcomes at the source.

– Section 4: Breaks down frequent accidents, from slips to vehicle interactions, and shows how to analyze precursors rather than people.

– Section 5: Concludes with a practical, time-bound plan and role clarity for leaders, supervisors, and frontline teams.

As you read, consider where your operations sit on the spectrum: Do you mostly react after an injury, or do you use leading indicators to steer away from trouble? The goal is steady, compounding improvement—incremental moves that set conditions for work to happen cleanly, consistently, and without surprises.

Safety Fundamentals: From Policy to Floor Practice

Safety programs thrive when they move beyond binders and turn into daily systems. A useful backbone is the hierarchy of controls, which prioritizes interventions from most to least robust: eliminate the hazard, substitute something safer, install engineering controls, apply administrative rules, and finally use personal protective equipment. In a warehouse, elimination may mean redesigning a pick path so pedestrians no longer cross a vehicle lane; substitution may replace manual strapping with a safer closure method; engineering might add guardrails, interlocks, light curtains, or barrier posts; administrative steps include traffic rules and standardized work; equipment like eye protection or gloves sits at the end as the last shield.

Comparing approaches is clarifying. Engineering controls, once installed, do not depend on perfect human memory, whereas administrative rules and equipment require ongoing attention and reinforcement. That does not make rules or equipment optional; it means they work best when higher-order barriers carry more of the load. For example, clearly separated pedestrian aisles with physical barriers reduce the frequency of close calls more reliably than signs alone. Similarly, racking anchored to spec and inspected on a set interval provides a sturdier defense than ad hoc repairs after a bump.

Consider these floor-ready practices that often pay off quickly:

– Harden corners, end-of-aisle zones, and dock edges with impact-rated barriers to convert severe events into minor contacts.

– Treat housekeeping as a control, not a chore: wet zones, stray wrap, and fragments of pallet stringers are classic slip and trip precursors.

– Stabilize workflows: surge-driven shortcuts tend to erode safe spacing, signal clarity, and hand placement discipline.

– Align maintenance with risk: small leaks or damaged casters create outsized hazards if ignored.

Data helps you decide where to focus. Track not only recordable injuries but also near-misses, facility damage, and first-aid cases. Map them to locations, times, and tasks. Patterns appear—perhaps the last two hours of a long shift show more incidents, or a particular lane produces frequent mirror strikes. Unlike general slogans, such patterns point to specific controls. A guardrail here, a mirror angle change there, a revised picking sequence—small edits that materially lower exposure.

Ergonomics: Designing Work to Fit People

Ergonomics asks a simple question: can a person perform this task repeatedly, for a full shift, without accumulating strain? In storage and fulfillment, risk amplifiers tend to cluster around four variables—force, posture, repetition, and duration. High-force lifts, awkward reaches into deep bins, repetitive wrist deviation at scan stations, and extended standing combine to produce fatigue and inflammation. Many injury logs confirm the outcome: strains to the lower back and shoulders, tendon issues in wrists and elbows, and knee discomfort escalated by twisting on fixed feet.

Comparisons guide design choices. A fixed-height table may work for one team member but force another into a rounded back; an adjustable surface reduces extreme postures across a diverse workforce. Lifting from floor to shoulder height demands far more effort than lifting between mid-thigh and waist; setting pallets on low risers keeps lifts within a stronger zone. Pushing typically allows the body to engage larger muscle groups more efficiently than pulling; reconfiguring carts and handle heights to enable pushing can lower peak forces. Similarly, breaking a 25-kilogram pick into two staged moves with a work rest reduces single-episode strain without adding much time.

Here are practical ergonomic steps that punch above their weight:

– Right-size containers: shallow bins reduce deep reaches; smooth rims protect forearms; molded hand-holds lower pinch forces.

– Bring work to the person: flow racks with slight pitch, turntables on pallet positions, and slide sheets minimize twisting and long reaches.

– Pace and rotate: short micro-breaks and task rotation across muscle groups help tissues recover without hurting output.

– Calibrate tools: scanners with neutral wrist grips, low-force tape dispensers, and well-maintained casters reduce repetitive load.

Observation skills matter. Watch for telltales like shrugging shoulders during reaches, frequent stepping to reposition in tight spaces, or tapping a wrist to shake off discomfort. These are signals that geometry or force is off. Involve the people who do the job; they often suggest elegant fixes, like moving heavy, high-turn SKUs to the golden zone, or adding a small staging shelf between floor-level pallets and the work surface. Pilot changes, measure pick rates and discomfort reports, then standardize what proves both safer and productive. Over time, you build stations and processes that fit people, not the other way around.

Accident Patterns and Root Causes: Seeing the System

Most serious events do not come out of nowhere; they travel in the company of warnings. In warehouses and industrial spaces, common scenarios recur: slips on moisture carried in from docks, trips over banding and broken pallet fragments, hand injuries in pinch points during wrap or strap removal, struck-by events at aisle intersections, and shelf or pallet instability during hurried picks. Vehicle-pedestrian interactions deserve special attention—low visibility near blind corners, silent electric vehicles, and mixed-pace traffic can align into a risky moment.

Listing triggers is a first step; analyzing why controls did not catch them is the breakthrough. Consider the “layers of defense” view: hazards pass through when multiple barriers have gaps that line up. A slip might involve a small leak, a missing drip tray, a late housekeeping round, and shoes with worn tread. A vehicle near miss may combine an obstructed sightline, a rush order pushing pace, and a muted horn in a noisy zone. Root cause thinking avoids blame and instead strengthens barriers so they fail less often and less completely.

Frequent contributors include:

– Unclear right-of-way rules at intersections and dock aprons, especially where pedestrians cross desire lines.

– Inconsistent load unit quality: broken boards, uneven wrapping, and unstable stacks multiply handling surprises.

– Lighting and contrast gaps: shadows that hide spills or make floor level changes hard to read.

– Process volatility: end-of-shift surges and irregular staffing raise cognitive load and error rates.

Comparisons highlight leverage. A convex mirror is helpful; a stop-and-look policy with marked stopping boxes is stronger; adding a barrier that enforces low-speed entry into intersections is stronger still. A sign reminding people to secure loose wrap is fine; a wrap removal station with cutters on tethers and a designated disposal bin makes the safe method the easy method. When you evaluate incidents, map the event backward: What task? What conditions? Which defenses existed, and which failed silently? This method turns stories into data, and data into design changes that persist.

Conclusion: Turning Insight into Action

For operations leaders, supervisors, and frontline teams, the aim is not a perfect plan but reliable progress. Start by choosing one high-risk flow—perhaps receiving, order picking, or dock transfer—and conduct a short walk focused on exposure, not compliance wording. Capture photo notes of hazards and ergonomic stressors, prioritize by potential severity and frequency, and pick three changes you can implement within 30 days. Pair a couple of quick wins (like stabilizing a slippery entry zone and adding a wrap removal station) with one structural change (such as reconfiguring a blind intersection or raising pallet positions off the floor).

Give the work a cadence. A simple loop works well:

– Week 1–2: Assess, involve the team, and prototype fixes on a small scale.

– Week 3–4: Standardize the changes, document the method with clear visuals, and train during normal shift rhythms.

– Ongoing: Track near-misses, first-aid cases, and small-damage events; review them in short, regular huddles; and adjust controls accordingly.

Clarify roles so momentum sticks. Leaders set direction and remove obstacles; supervisors coach and reinforce standards; workers provide insight and surface weak signals before they grow. Celebrate hazard removals and ergonomic upgrades the same way you would a production milestone—they both protect flow. Over a quarter or two, you’ll see downstream effects: steadier output, fewer surprise stoppages, and higher morale. Most importantly, you create conditions where good days are uneventful for the right reasons: hazards removed, tasks designed to fit people, and accident patterns cut off long before they align. That is how safety, ergonomics, and prevention move from posters to practice—and stay there.